The Port of Vancouver has the ambitious goal of becoming the most sustainable port in the world. A significant part of the path towards this goal is connected to sustaining a healthy ecosystem for the local biodiversity. The port is developing a myriad of actions to protect the local species and managing the port lands and water in a sustainable way, including a broad Habitat Enhancement Program developed over the past 30 years. In this interview we will learn about the different projects implemented to protect and enhance the local biodiversity.

Interview with Duncan Wilson, Vice-President of Environment and External Affairs at the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority

AIVP – Vessel traffic is at the origin of some disturbances for animals, such as underwater noise or ship-generated waves. We have heard of your motivation to reduce underwater noise, mostly linked to famous initiatives such as the “ECHO” Program, aimed at reducing such negative effects. Could you tell us more about this program?

Duncan Wilson, Vice-President of Environment and External Affairs, Port of Vancouver – The Salish Sea, where the Port of Vancouver is located, is a richly diverse area of the Pacific Ocean that is home to a vast array of marine life including some endangered species like the Southern Resident killer whale (SRKW). With thousands of ships transiting through this area en route to the Port of Vancouver, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority launched the Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program in 2014 to better understand and reduce the cumulative effects of shipping on this local whale population.

Recognizing that underwater noise from commercial ships can interfere with the southern resident killer whales’ ability to hunt, navigate, and communicate, the program encourages ships to voluntarily slow down or stay distanced in order to reduce underwater noise while transiting through critical southern resident killer whale foraging areas.

Since the first slowdown in 2017, more than 6,000 ships have participated in the ECHO Program’s voluntary underwater noise reduction initiatives, which span across 74 nautical miles of the Salish Sea. In 2020, these initiatives helped achieve a nearly 50% reduction in underwater sound intensity in certain southern resident killer whale foraging areas.

We are tremendously proud of the broad awareness the ECHO Program has helped generate about the issue of underwater noise, and we are especially excited that a sister program – called the Quiet Sound program – is launching in the state of Washington, USA, inspired by our program. We are working to encourage further underwater noise reduction efforts at ports around the world.

AIVP – Invasive species are one of the most dangerous threats to local biodiversity. It is a common phenomenon in port cities welcoming many ships, carrying ballast waters with foreign species. It has been evaluated that around 30-35% of endangered biodiversity is due to invasive species. What policies are you implementing to prevent such issues?

Duncan Wilson, Vice-president of Environment and External Affairs – We monitor the lands and waters within our jurisdiction for invasive plants and other aquatic invasive species and conduct management and removal efforts as appropriate, as well as annually contribute to the physical and chemical removal of spartina, an invasive cord grass that has impacted our shorelines.

To prevent the transfer of invasive species from ships entering our local waters, we were the first port in North America to prohibit in-port ballast water exchange without prior mid-ocean exchange. This practice has become the basis of the Government of Canada’s guidance and has been adopted by many other countries as one of the best available options to reduce the risk of introducing invasive species.

All vessels calling the Port of Vancouver must meet the requirements set out in the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) Ballast Water convention, which requires vessels to have an approved ballast water treatment system onboard or conduct ballast water exchange. In addition, all projects with the potential for invasive species impacts (such as propeller polishing, for example) must undergo a pre-inspection survey to identify the extent of the marine fouling on the propellers.

We’re encouraged by the progress the shipping industry has made towards the development of anti-fouling technology that prohibit or limit the growth of marine organisms on vessel hulls. In particular, the IMO 2011 Guidelines for the control and management of ships’ biofouling to minimize the transfer of invasive aquatic species provide guidance on anti-fouling. As per Canada’s federal Ministry of Transport (Transport Canada), we encourage vessels to voluntarily follow the IMO’s biofouling guidelines as best practices for invasive species management.

AIVP – The Habitat Enhancement Program includes many habitat restoration projects, including the new Brighton Park Shoreline Habitat Restoration Park, which combines new public spaces with restored wetlands. Can you explain a bit more about this project and its reception by the community?

Duncan Wilson, Vice-President of Environment and External Affairs – Our Habitat Enhancement Program focuses on creating, restoring and enhancing fish and wildlife habitat in order to provide a balance between a healthy environment and future development projects that may be required for port operations.

One such completed project is the New Brighton Park Shoreline Habitat Restoration Project, which enhanced fish and wildlife habitat in an area of the Port of Vancouver called Burrard Inlet, and increased public access to the bountiful nature within it. In partnership with the Vancouver Park Board, the Musqueam First Nation, Squamish First Nation and Tsleil-Waututh First Nation communities, we restored and enhanced a historically filled foreshore and upland area by providing high-value habitat for a broad range of fish, birds, and other wildlife species.

The creation of a tidal wetland provides critical habitat in Burrard Inlet for juvenile salmon that migrate along the shoreline as they head out to sea, while the planting of various west coast native plant species – approximately 25,000 salt marsh plugs, 200 native trees, and 4,000 coastal shrubs – has reintroduced plant biodiversity at the newly constructed wetland. Construction was completed in 2017 and, as is the case with all habitat enhancement projects, we monitor the site annually to ensure the project continues to meet its biophysical objectives.

AIVP – Maplewood Marine Restoration Project is one of the ongoing initiatives in the Port of Vancouver to protect the local biodiversity. This project also includes a broad engagement with different social groups and public discussion. How do you developed this social engagement and how was this project implemented?

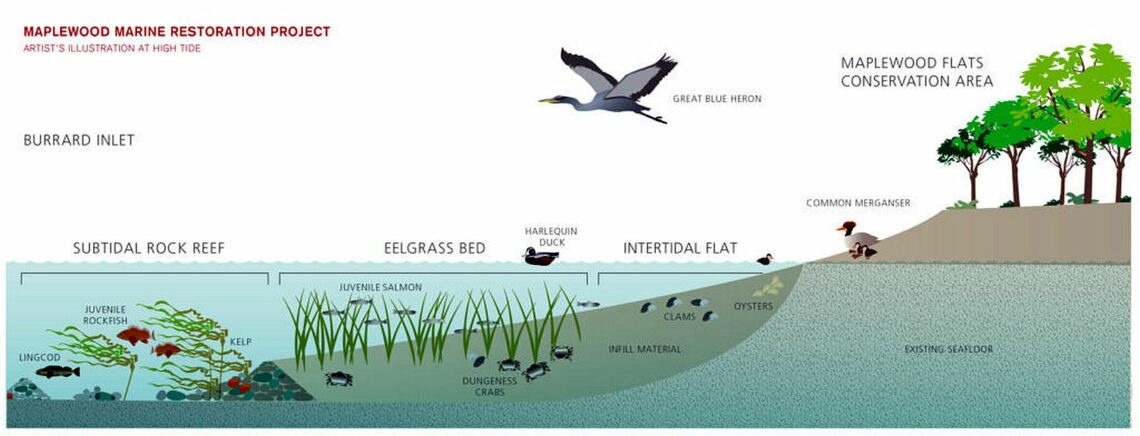

Duncan Wilson, Vice-President of Environment and External Affairs – The Maplewood Marine Restoration Project is located in the Port of Vancouver on the north shore of Burrard Inlet in a marine site that was identified as a restoration priority by a local Indigenous group, the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation. In alignment with the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation’s Burrard Inlet Action Plan, and due to the site’s industrial past, our project focused on restoring the low-diversity marine habitat into a higher-diversity marine habitat for fish, birds and other wildlife.

The project included something that has never been done before in Burrard Inlet: the transplanting of approximately 125,000 eelgrass shoots to create a 1.5-hectare eelgrass bed. This work was completed through ongoing collaboration with Tsleil-Waututh Nation, from project planning through construction, which wrapped up in August 2021. We also thank Musqueam First Nation and Squamish First Nation for their participation and involvement.

Our approach to public and stakeholder engagement is based on two-way communication and open dialogue, working together to ensure the community, the environment and the economy are all considered during project planning. As part of this project, we engaged various stakeholders including local residents and businesses, government, environmental and community liaison groups, and other municipal groups.

The port authority has completed feasibility work on over 100 hectares of potential habitat enhancement. We work with Fisheries and Oceans Canada and consult with Indigenous groups, all levels of government, neighbouring communities, and other regulators on potential projects. This allows us to make sure the interests of all parties are considered, for the benefit of everyone.

AIVP – The Port of Vancouver is also planning an ambitious port expansion, with the Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Project. There are several offsetting actions planned, to protect tidal marshes, eelgrass, and salmon populations.

Can you tell us more about these projects, how you have structured them and what is their importance for the new terminal plans?

Duncan Wilson, Vice-President of Environment and External Affairs – Our approach to offsetting environmental impacts of the Roberts Bank Terminal 2 Project is informed by over a decades’ worth of environmental research into the proposed project, including over 77 individual studies resulting in 35,000 hours of fieldwork by over 100 professional scientists and engineers.

This work identified key opportunities for protecting fish and fish habitat from potential project-related effects during construction and operation and has informed a number of mitigation measures to avoid, reduce, or offset project-related effects. In addition to constructing the terminal away from sensitive intertidal habitat in deep waters, we are proposing additional mitigation measures related to juvenile salmon, including a reduction of the terminal footprint and modifications to the project design to facilitate fish passage through north and south ends of the project.

For example, we are proposing to build 86 hectares — approximately 163 football fields — of offsetting habitat developed in collaboration with Indigenous groups to support priority species like juvenile salmon, Dungeness crab, and other wildlife. This includes a variety of habitat types and advances priority habitats identified by Indigenous groups, which are reflective of their vision for habitat enhancement in the area.

AIVP – The projects developed by the Port of Vancouver to protect the biodiversity are not only relevant for the environment, but they are also an opportunity to work with First Nations/Indigenous groups. How is this collaboration structured?

Duncan Wilson, Vice-President of Environment and External Affairs – Building relationships with First Nations and Indigenous communities is not only part of our federal mandate — it allows us to learn from their expertise, cultivated over thousands of years of living and prospering along the Salish Sea, Burrard Inlet and Fraser River.

Through our shared interest in protecting the lands and waters within the Port of Vancouver’s jurisdiction, we work together with local Indigenous communities to help build and maintain the healthy environment of their territories. As a result, we and local Indigenous communities have been able to undertake mutually beneficial projects within the Port of Vancouver, such as the New Brighton Park Shoreline Habitat Restoration Project, to support the health of the lands and waters we share.

Along with these principles, the port authority recognizes the importance of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and is committed to aligning with the federal Principles Respecting the Government of Canada’s Relationship with Indigenous Peoples within its mandate provided for in the Canada Marine Act.