The issue of sustainable mobility is without doubt one of the prime challenges for port cities. From international shipping routes or continental freight corridors to the urban flows and passenger’s movements, all these very different scales are interconnected and need to by harmonized. In this article by Systematica , we can learn from two Italian cases and their most recent projects to make mobility more sustainable.

Systematica has been an active member of the AIVP since 2019.

Sustainable mobility in port cities is essentially a story of integration. On the one hand, integration of local movements within international maritime corridors to ensure the seamless functioning of logistics and passenger routes at the global scale; on the other, it is the integration of port and city, which pivots not only on the coordination of land uses and the accommodation of new co-dependent functions between traditionally isolated realms, but also on the integration of local port activity within the wider mobility system in their respective urban and metropolitan contexts.

Systematica’s involvement in the field of mobility for over 30 years has given the firm ample opportunities to contend with a diverse range of mobility problems in port cities of the Italian, European and international contexts alike. To elucidate on key insights from practical expertise, we explore the complexities of mobility management vis-à-vis the urban framework in port cities through the planning experiences of two major Italian capitals, Genoa and Venice, whose diverging contemporary trajectories are further enriched by historical conflict in 13th and 14th century wars over control of the Mediterranean Sea.

The Cities in Figures

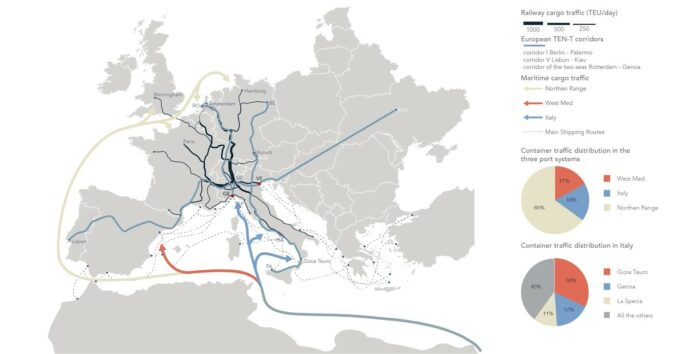

Today, the two port cities (and their ports) have different competitive advantages: Genoa’s port activity is more dominant for logistics and ferry movements, while Venice’s port activity has higher cruise passenger volume. Genoa holds 17 percent of all container traffic in Italy, the greatest generator of container traffic in northern Italy and second only to Goia Tauro at national scale. Cargo movements from Genoa’s main ports in 2019 amounted to 68.1 million tons, which, despite a 3.2% drop from 2018 figures, is still close to thrice Venetian cargo movements, which stood at about 24.9 million tons in 2019. Conversely, Venice’s notorious cruise passenger movements of 1.4 million – the object of much conflict and debate in recent years – are half again as many as Genoa’s 0.9 million, unsurprisingly given the city’s number one national rank for visitors of tourism. When we look at ferry passenger movements, Genoa’s figures (2.1 million) tend to dwarf those of Venice (0.2 million) tenfold. Ferry movements for both cities, however, are relatively low in comparison to southern Italian ports surpassing 10 million movements at their peak.

Considering differences in scale, it is important to note that Venice’s land cover of around 158 square kilometers (roughly 40% of the total metropolitan area) is nearly half the surface area of Genoa (240 square kilometers). Likewise, Genoa’s population of 570 thousand inhabitants, with a population density of 2,377 inhabitants per square kilometer is significantly higher than Venice’s 260 thousand inhabitants and density of around 623 inhabitants per square kilometer. However, we have to consider Venice’s skewed balance between inhabitants and visitors, with a ratio of 167 tourists per resident, compared to 24 tourists per resident in Florence, for example. Taking visitors into account would significantly raise the effective person density in the city. This reality has major implications for the city’s mobility system, which is currently organized to a very large extent around the movements of tourists. The road network, railway terminals and water taxi systems all respond primarily to tourist demand rather than the needs of the local population.

Port Exit: Urban Consequences of Containerization

Both cities’ socio-economic histories rely largely on their strategic locations along major international trade routes. Both cities were also among the first to industrialize in the country, with Genoa dubbed the ‘City of Steel’ for its remarkable industrial expansion in the 18th Century. With the rise of containerization in the second half of the twentieth century, new port technologies made the old ports of both cities inadequate for effective operation, prompting relocation away from the city core. In 1969, Italy’s first, and one of Europe’s first two container terminals was opened along Genoa’s western coastline. In contrast, the city center – Europe’s largest – fell into disrepair. A number of regeneration investments in the 1990s, including Renzo Piano’s Affresco waterfront project developed to reconnect port and city, led to a gradual upgrading of the city core. Following a city marketing urban planning strategy, Genoa’s touristic attraction increased fourfold in a span of 5 years (1999-2004).

Alternatively in Venice, new technical requirements of motor navigation rendered the morphology of the archipelago’s narrow canal system inadequate for navigation, pushing manufacturing and commercial port activities in-land. Rail connections to Milan further consolidated an industrial center of gravity to the west, as the historic center gradually turned into a touristic hub. The historic center’s port became limited to passenger transport, overwhelmed by cruise tourism activity. While Genoa’s touristic growth may have been the city’s saving grace in the aftermath of spontaneous port evolution, Venice’s touristic concentration is its choke point. More than any other world city, Venice’s experience demonstrates the negative consequences of the complex dynamics of port evolution, heritagization and excessive urban tourism pressures.

Urban Structure and Port Configurations

Today, the urban structures of both cities play a major role in the development of their port activities and capacities. Genoa’s particular orographic configuration, bounded by mountains a few hundred meters from the sea, coupled with intensive urbanization surrounding its ports, are conditions that make it difficult to extend space for port operations. The establishment of the Rivalta Scrivia dry port 75km from the city only partially compensates for this reality. In comparison, Venice’s strict division of functional land uses between in-land industrial activities and touristic services on the lagoon islands has physically manifested itself in the functional division of its two main ports: the Marghera side and the Venice side. The overtouristification of the islands and associated pressures on its cruise terminal can have negative long-term effects on the city’s overall port efficiency and management, as has been made visible in recent years.

Global Investments and Major Strides

The need to reconsider capacity limits of both port cities comes at a critical time when continental and regional investments in freight networks are marking an increasing role of mediterranean ports in strategic traffic corridors between Asia and Europe. Chief amongst these developments is the expansion of the Suez Canal in 2015, effectively doubling the capacity of traffic flowing between European and Asian ports. As underlined by Massimo Deandreis, General Manager of the Center for Economic Studies and Researches (SRM), Italy is a ‘natural bridge’ for energy and logistics between Europe and the Southern Mediterranean region due to its strategic location along key global corridors.

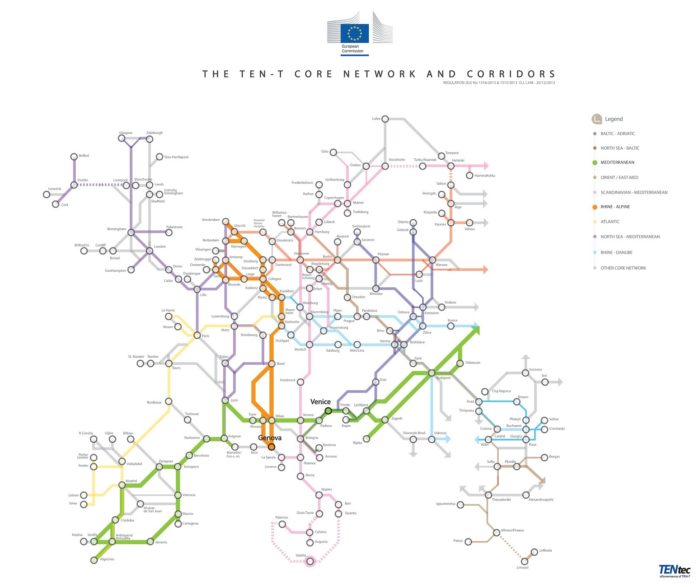

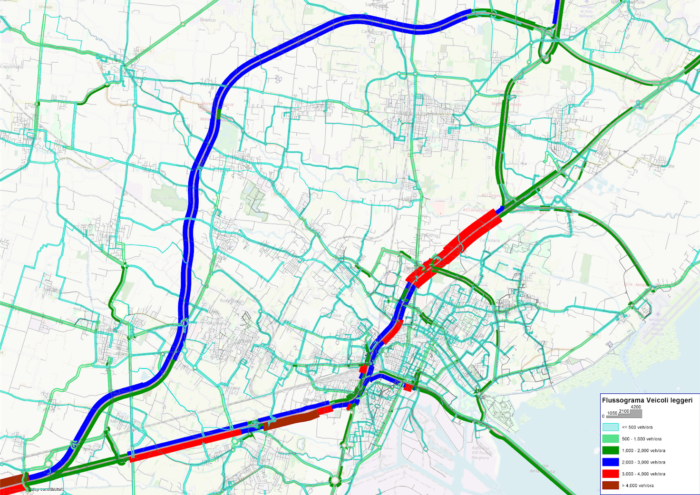

Major strategic rail projects, such as those carried out under the European Commission’s Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) policy, further augment chances for key North-Italian ports such as Genoa and Venice to advance their positions in the logistics sector by enhancing intermodal connections (corridors 24 and 5, respectively). As evidenced by the Ponte Morandi incident of August 2018 in Genoa, the bridge collapse did not only paralyze road traffic, but had wide ranging implications on the economy of the city through a ripple effect on integrated mobility systems. In Genoa, 70 percent of marine freight continue their land journey through road infrastructure, compared to only 20 percent by rail. With a major axis in the chain of logistic movements severed, shipments arriving at Genoa were redirected to other ports to compensate for reduced capacities. Strengthening intermodal diversity by balancing rail-based and road-based connections can have wide-ranging operational benefits for the entire system.

Once completed, the Rhine-Alpine corridor connecting Genoa to key North Sea Ports in Belgium and the Netherlands, one of the busiest freight corridors in the continent, will enhance north-south connectivity. In contrast, the Mediterranean corridor which passes through Venice will strengthen the east-west axis, from the Hungarian-Ukranian border all the way to Spain. Furthermore, major investments are pouring into the construction of the Swiss AlpTransit tunnels at the Italian border under the NTFA (Nuove Trasversali Ferroviarie Alpine), as well as the newly completed Mount Ceneri base tunnel in Switzerland, which effectively completes the NRLA (New Railway Link through the Alps). The development of trans-continental high-speed railway (HSR) lines, in combination with the new Alpine tunnel connections create sizable time-space compression gains. In effect, these two critical investments are projected to yield huge progressive macroeconomic benefits to the Italian economy in the next 5-10 years.

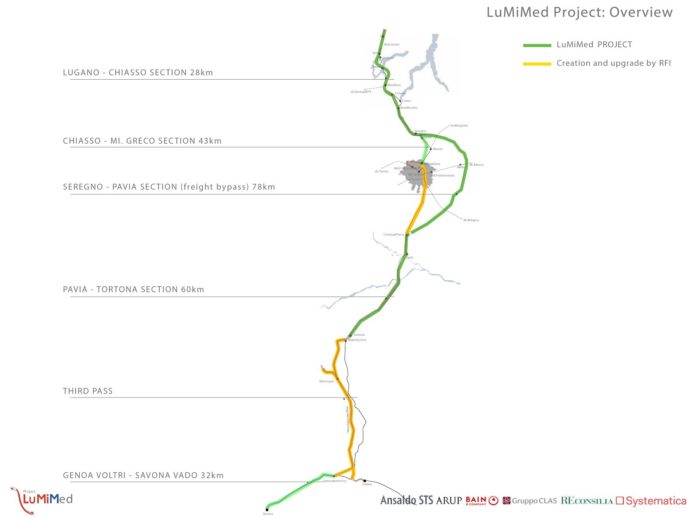

In close collaboration with other major partners, Systematica worked on a hypothesis for future scenarios in the Ligurian context, advancing from the two very important innovations in the system elaborated above. The augmented capacity of the Suez canal has increased the maritime traffic in the Mediterranean both in terms of ship units and in ship size, with the result of an increased and lower barycentre of the maritime traffic. At the other end, the inauguration of the Gotthard tunnel in Switzerland has created the possibility of a direct and fast connection between Genoa and the area to the north of the Alps within a radius of 4,000 kilometers. The LuMiMed project, of which Systematica is a partner, offers potentials to optimize operations along the Rhine-Alpine corridor connecting Genoa to the north.

By means of the implementation of a strong rail connection between Genoa, Milan and Lugano, high speed passenger trains would connect Genoa and Zurich in under three hours, while ensuring a high capacity line for commercial convoys. An economic estimate has valued returns in almost two billion dollars per year. The direct and induced profits generated by this connection with a rapid economic investment return would be significant; this without computing all social and ecological benefits.

The rail connection alone, however, is not sufficient to achieve the desired results. A good local connection between the rail station and the rest of the city via a transit-oriented policy, including the port as one of the main areas of focus in an efficient, clean, sustainable connection, is conditio sine qua non in order to realize true benefits. At the same time, the reorganization of the port, starting from the docks with the possibility to load 500-750 trains quickly and efficiently, is a must to obtain time and cost reductions and reduce negative impacts on the city (more modern trains, less trucks, more flexibility).

This rail connection innovation offers a golden opportunity to coordinate the different plans of intervention in the city, involving all stakeholders and administrations in a medium-long term plan for the sustainable development of the territory. Upon implementation, the plan would ultimately contribute to more industrial opportunities, more jobs, increased mobility and accessibility at the city scale and lower emissions and noise pollution.

Local Investments and Mobility Plans

Several local projects and investments compliment the goals of the LuMiMed project and other European rail-based programs. The Western Liguria Sea Port System Authority (AdSP) is also invested in a critical intermodal project to deliver a final railway mile to allow for a significant increase in the modal split and daily in-coming/out-going trains. The model projects a 160% increase from current figures along the Genoa and Savona-Vado lines. Co-financed projects between the Authority and European Union institutions focus on environmental performance, intermodality and digitization of logistics ports and networks. The E-BRIDGE project, for example, co-financed with the European Union, aims for the complete digitization of data exchange in the Port of Genoa.

In addition to this, the Genoa Decree for the Recovery Action Plan enacted in the aftermath of the Ponte Morandi Bridge collapse is a major investment program of an approximate cost of two billion euros. Through the Recovery Plan, Genoa is currently undergoing an extensive restructuring programme focused on enhancing maritime, air, rail and road accessibility, in addition to redeveloping industrial and waterfront areas. According to a recent progress report, the pillars of the plan have all either been completed or are already in progress.

Current and short-to-medium term projects in Venice carried out by the Port System Authority of the Northern Adriatic Sea (AdSPMAS) have similar focal points (such as intermodality and a switch to renewable resources) and some particular to its unique situation. Specific focal points include maintaining accessibility through continuous excavation works in the port canals (such as the 20 million euros excavation project currently underway in the major navigation channels), protection of the city against flooding (through the ongoing MoSE project) and upgrading works for old and dilapidated ports. Long-term goals include the operation of offshore systems for freight and passenger transport. The SUMP (Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan) of Venice, which Systematica is currently involved in, sets 17 macro-objectives for the city focused on efficiency, safety and environmental and socio-economic sustainability. It aims to grapple with the intense urban development of areas like Mestre and contend with large infrastructural projects such as the extension and railway connection of the international airport, the development of the Marghera Port and the relocation of the cruise terminal.

The project for the relocation of cruise terminals in Venice from the city center to the Porto Marghera First Industrial Zone is an ongoing debate. If realized, the project will involve massive infrastructural works to redirect large vessels from the Lido to the Malamocco inlet. Triggered by the Costa Concordia disaster in 2012 when the large cruise liner ran aground on the Giglio island off the coast of Tuscany and capsized, an inter-ministerial decree to ban the entry of vessels over 96,000 tons through the San Marco basin was enacted. The more recent cruise liner crash in the docks of Venice in June of 2019 fueled the need to commence the project, although the exact logistics of the project are complex and will have major impacts on the livelihoods of workers in the cruise tourism sector.

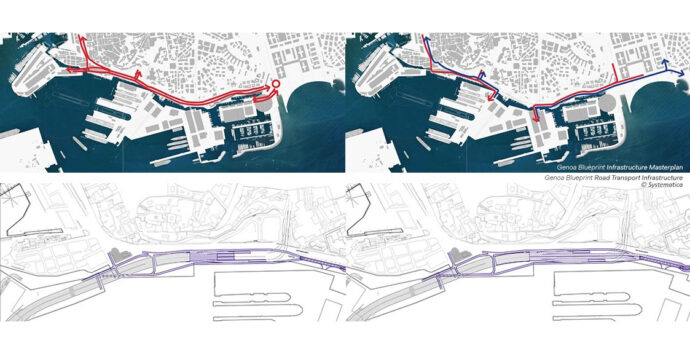

Urban regeneration initiatives in both cities help support the port activity and promote well-balanced port-city relations. The Blueprint waterfront masterplan in Genoa, which Systematica had the opportunity to support, is a waterfront project by Renzo Piano focused on the promenade between the Historical Port and the area of the Exhibition Fair, effectively culminating the design of the old port area. It focuses on replacing volumes of cement with new urban functions to seamlessly coincide with existing harbor areas. In line with the masterplan’s aims, Systematica proposed two infrastructural scenarios for the project: the first centered around the construction of an underwater tunnel, while the second envisioned the construction of an inland arterial road, to relieve pressure from and ultimately replace the currently congested coastal flyover.

Alternatively, one of the critical waterfront regeneration projects in Venice is the VEGA masterplan (the Venice Gateway for Science and Technology) located in the ex-industrial site of the Porta Maghera area. It was conceived in 1993 with the purpose of recovering industrial brownfields in the First Industrial Zone for entrepreneurial initiatives, research and innovation to serve the entire metropolitan area. The project is a long-term and complex one due to the mere scale of the project and the number of stakeholders involved in one of the largest ex-industrial sites across Europe.

Final Reflections

A comparative reading of these two important port cities situated along the eastern and western coasts of Italy highlights their very different complexities despite their comparable prominence on the global arena, their rich historical connections with the sea and the importance of their positions in wider continental scales. We understand that the port is a very complex and pivotal asset within each city, and how we grapple with the necessities to mediate between port and city goals, as well as integrate them, is an important question to keep in mind.

Perhaps more than any other port city, the city of Genoa must closely coordinate the plans of urban and port authorities. Because of limited land resources, developments in the port areas must consider impacts on the city and vice versa. Likewise, the protected heritage status of the city of Venice, its physical flooding risks and metaphorical flooding with tourists compete with the operational needs of the ports. These issues make it all the more reasonable to adopt a comprehensive planning approach between respective authorities, and to develop strategic long-term planning visions beyond the traditional 20-year horizon.

The moment of the pandemic has brought an everpressing need to focus on resilient and multi-disciplinary planning structures. While Port Authorities report drops in maritime freight movements in the range of 10-20% in past months compared to the same period last year, passenger traffic dipped by upwards of 60%; cruise movements alone experiencing close to 90% shortfalls. The importance of economic diversification of port cities is thereby emphasized by the aggravated situation of the pandemic.

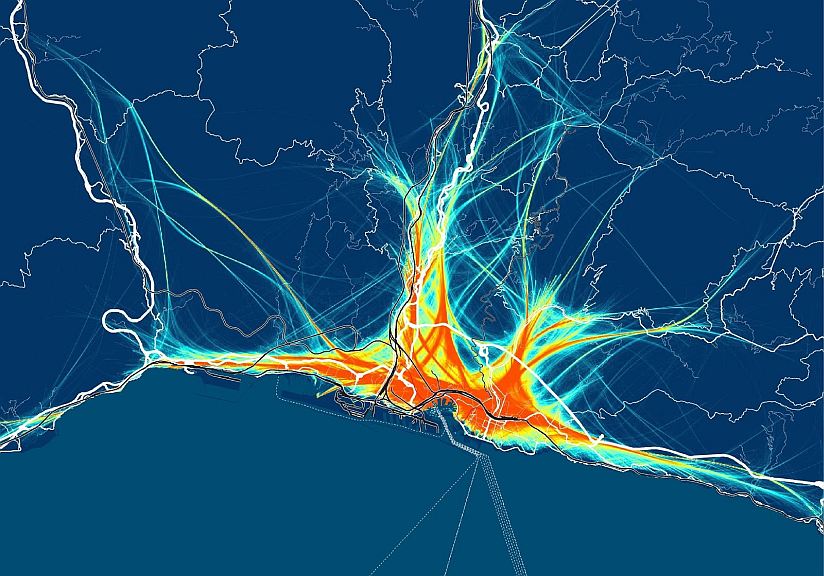

The emergency situation also places emphasis on the importance of promoting data-driven approaches in port operations. Efforts to digitize operations would enable constant monitoring and demand-responsive action, needed within the state of emergency and beyond it. Digitized operations would also induce a series of macro and micro-scale efficiencies through smart solutions, alleviating some of the burden of limited land resources, whether in orographically confined Genoa or water-surrounded Venice. Systematica’s own current experience working on the infrastructural design of the Genoese Port of Voltri – one of the most important European ports for container freights – attests to the power of data optimization. Congested areas in the system revealed by macro-simulation analysis demonstrated that the effectiveness of operation management is fundamental to a port’s success.

The combined effects of increased intermodal capacities, extensions of vital logistic and passenger corridors and optimized data solutions would create synergistic conditions that have the potential to bring key Mediterranean port cities to par with northern competitors, and restore Italy’s position as a central anchor along strategic corridors of the global blue.